Consequence Management: A Neglected Aspect of Nigerian Public Financial Management

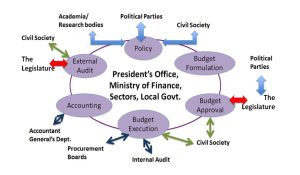

Public Financial Management (PFM) covers numerous aspects of public decision-making, public policy, fiscal management, revenue and expenditure policy, planning and budgeting. The objectives of PFM include Allocative Efficiency, Aggregate Fiscal Discipline, and Operational Efficiency. These objectives in and of themselves have links to broader macroeconomic objectives, and while countries can decide their own rules, general rules apply to most jurisdictions. These directives are in place to ensure the government’s actions are done predictably, in an orderly manner, and in a way that warrants problems—when they arise—can be traced to breaches of guidelines.

Also, there should be investigation and prosecution when it has been demonstrated that the stipulations for these provisions have been broken. This predictability and certainty strengthen the system and empower the rule of law, creating a sense of reliability in the regulations and the system they operate in favor of local and international actors. The figure below describes the PFM cycle and the groups and entities involved.

While various entities and actors are involved in the cyclical diagram above, the persons and groups have obvious goals that will vary within sound PFM rules. Since 2004, the Nigerian Federal Government embarked on a series of reforms in the rudiments of public finance, which have led to substantial savings and the elimination of a significant number of ‘ghost workers’ from the government’s personnel database. While these gains may be noticeable, attempting more technical (or domain-specific) PFM reforms in developing countries is far from straightforward.

Empirical evidence is often equivocal on the direction of causality between macroeconomic variables, political variables, and PFM reform elements. Despite this, the gains from PFM reforms (resulting in improved capacity of the civil service, government savings, and the signals to the domestic and international private sector) are compelling reasons for its continuance as they can improve the prospects of developing and emerging economies.

The Office of the Auditor General of the Federation (AuGF)

The Office of the Auditor General of the Federation is the essential entity that ensures the accuracy, efficiency, and integrity of government spending. Still, despite the Auditor General’s high profile, the office’s impact has left much to be desired. For instance, just last year, the AuGF executed a performance audit of the Federal Emergency Road Maintenance Authority (FERMA) on monitoring the maintenance of federal roads in Nigeria from 2016–2018.

While the AuGF’s findings in the FERMA report were consequential, there was no traction for implementing the recommendations. Still, even if there was implementation, the lack of regularity in performance auditing means that improvements cannot be measured promptly. This is even though the performance review itself came on the heels of calls by the National Assembly to scrap the agency.

The AuGF also suffers from a general lack of compliance with directives by MDAs. It has been reported that despite indicting MDAs for improper spending (running into billions of naira) and unsubstantiated balances, there has been minimal to little reprimand for errant MDAs. The reasons behind the routine non-compliance with the AuGF’s queries range from lack of a Federal Audit Service Law to inadequate funding and poor accommodation for Audit Officers. This creates a problematic situation as the mere compensation of these officers is not guaranteed and does not bode well for retaining a capable and skilled workforce.

However, the chief problem is the inability, refusal, and failure of the relevant Minister (whom the errant MDA reports to) or the President to enforce compliance with the AuGF’s queries. This consequential report, directly meant to support the AuGF’s work, is routinely delayed. There may be light at the end of the tunnel, at least concerning auditing at the sub-national level. In a twist of ‘behavior,’ the federal government should learn from the states as the former ought to toe the line of the states, reconsider the Audit Bill, and pass the same to empower the AuGF.

The Budget Office of the Federation (BOF)

Contained within the Ministry of Finance, Budget, and National Planning, the BOF is instrumental in overseeing a significant portion of the national budget process. From preparing the Medium Term Expenditure/Revenue Framework (which informs the annual budget) to designing the Executive budget proposal (flowing from earlier MDA proposals) and then monitoring and evaluating the implemented budget, the Budget Office is a consequential fiscal policy office.

Because of this responsibility and budget function discharge of the Presidency, one can construe that the BOF has supervisory responsibility and a corresponding power to enforce compliance with its regulations and guidelines. However, the BOF, in reality, elicits minimal compliance from MDAs despite distributing Budget Circulars that contain guidelines and provisions for formulating the budget.

While the BOF routinely aims to improve the capacity of MDAs, it is not winning the battle for compliance. As it stands, the BOF has the Budget Circulars and the Budget Bilateral Discussion Sessions as avenues through which the MDAs can have their proposals vetted, and the responsible government officials corrected and rightly guided. It is, therefore, troubling that the BOF cannot use these two platforms to insist on compliance from the MDAs.

This is significant, considering the BOF’s seeming silence regarding Government/State-owned Enterprises budgets. Many GOEs’ budgets do not pass through the BOF, nor does the BOF provide any input into their budget process. It is proposed that while the BOF, the Minister of Finance and Civil Society, push for the passage of the Budget Bill to law before the new NASS, the following mechanism can be set to ensure compliance with the Circulars from the BOF.

It is proposed that the President issue formal Executive Orders on Budget Management that mandate compliance with instructions from the BOF. As the latter represents the President and his function of budget management, it follows that the Office of the President can send a clear signal to MDAs on the level of compliance required. Flouting of the order should be followed by swift sanctions of suspension of the head of the agency (the latter, who functions at the President’s pleasure) and devolving powers to the second in command.

The National Assembly of the Federal Republic of Nigeria

The National Assembly is the republic’s chief appropriation body and the principal federal lawmaking body. This lawmaking function is part of the more critical duty of serving as a ‘check and balance’ to another arm of government: the Executive. The lawmaking function extends to not only the passage of laws but also the amendment of existing laws and the repeal of laws that do not represent the current government’s position or national aspiration. Several Nigerian laws relating to PFM require urgent attention, for instance, the Audit Law (1959) and the Fiscal Responsibility Act, 2007.

Also, the NASS Appropriation function requires review. The Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of both upper and lower houses in the NASS must amend the Public Accounts Committee Act, 2004, specifically section four of the Act. This amendment will allow the PAC the time to conclude deliberations on the AuGF report and other statutory bodies.

The amendment should also provide clear guidelines and penalties for the PAC where breaches occur. Currently, the PACs of both houses theoretically have unlimited time to ‘review’ and complete their deliberations on the AuGF report. This creates an absurd situation, regularly exploited by the NASS, where reports on the Federal Government’s finances become public only years after elapsing. This does not demonstrate that the NASS is concerned with the timeliness or regularity of public reporting.

In summary, the NASS has been unable to serve as a reliable monitor to the Executive—hence the question of why it even exists. NASS Oversight Performance is only one of its significant roles (the other two being Representation and Lawmaking), but this performance has been lackluster. Though the legislature is powerful, there are entry points for improving the quality of their governance. These remedies may not elicit immediate change, but such monumental change is not often known to happen swiftly.

The Administration of Justice—Investigation and Prosecution

The judiciary is the arm of government responsible for adjudicating the breach of PFM laws (effectively, the delivery of punishments or ‘consequences’) where circumstances allow. This responsibility to adjudicate and dispense justice, in turn, is supported by the Executive through the instruments of its investigatory and prosecutorial agencies: the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) and the Independent Corrupt Practices Commission (ICPC), among others. While these institutions can provide evidence of numerous investigations and even convictions (though this is debatable), it has been observed that it is difficult to appropriately measure their effect on Nigeria’s PFM system and even anti-corruption.

In any case, EFCC and the ICPC’s effectiveness is hampered in other respects. For instance, the ICPC investigates corrupt practices relating to public servants and public duty bearers. While they possess relatively sufficient powers to investigate and prosecute, they cannot convict. Even if the ICPC recommends dismissal, the wrongdoers can still be reinstated to their jobs. This is because the power to determine the fate of any Civil Servant resides with the Civil Service Commission and the Head of Service. This creates a curious situation where the ‘consequence’ is delayed or deferred and does not depict a system serious about punishment.

The current administration has an urgent mandate to ensure that corruption in Nigeria is reduced considerably. While it can be argued that PFM is only an incidental mandate of the two agencies, they nonetheless have some form of engagement with it. The EFCC and ICPC need to collaborate with other agencies and institutions in the PFM space to discharge their functions optimally. The EFCC, ICPC, Fiscal Responsibility Commission, the AuGF, and the BOF should frequently consult and partner with one another.

Conclusion

Though powerful and influential, the above Offices and Institutions have been unable to properly secure governmental integrity in a dynamic way that positively reinforces itself. This is despite various mechanisms and frameworks (including constitutional provisions and principles of justice and good governance) that can ensure compliance with PFM rules and regulations. While it is essential to see that the breach of rules follows a process and that defaulters face a form of penalty, it is crucial to identify the underlying causes.

In any case, the importance of all these rules and normative expectations must be viewed within the context of national planning and growth—key guiding notions for optimal public governance. There may be some skepticism at the potential for improved public governance since governments (at all levels and all arms) are powerful and impactful. However, this does not mean that citizens are powerless. It means that citizens must understand their role in keeping government institutions in check. This activity can be on the platform of citizens’ groups, CSOs, or combinations of both. Governments can be positioned to work in the interest of citizens, but citizens must be aware of the tools and institutions they can leverage.