Undoubtedly, Africa is endowed with abundant natural resources, from agricultural to mineral resources. However, Africa’s resources have been the subject of tussles by several interests. Through the age of mercantilism and the slave trade (that determined the economic and military might of colonial powers), to current economic realities, when mineral resources dictate the global economy, the struggle for Africa has been the fight for its resources. The famous Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 is typical of these dynamics. Although 140 years have passed since the General Act of Berlin was signed by colonial powers, and in that time, countries on the continent acquired their independence from colonial rule, self-determination in the utilisation of its resources is significantly limited.

Undoubtedly, Africa is endowed with abundant natural resources, from agricultural to mineral resources. However, Africa’s resources have been the subject of tussles by several interests. Through the age of mercantilism and the slave trade (that determined the economic and military might of colonial powers), to current economic realities, when mineral resources dictate the global economy, the struggle for Africa has been the fight for its resources. The famous Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 is typical of these dynamics. Although 140 years have passed since the General Act of Berlin was signed by colonial powers, and in that time, countries on the continent acquired their independence from colonial rule, self-determination in the utilisation of its resources is significantly limited.

According to the UN, the continent accounts for approximately 12% of the world’s crude oil reserves, largely concentrated in Nigeria, Libya, Algeria and Angola. 8% of the world’s natural gas can be found in Africa, while the continent holds 30% of mineral resources. The largest reserves of cobalt, diamonds, platinum and uranium in the world are in Africa. More than 50% of the world’s gemstone supply is sourced from Africa with Botswana responsible for at least 70% of global deposits. With major contributions from countries like Ghana and South Africa, Africa leads the world in gold output, producing over 1000 tonnes in 2023 according to the World Gold Council.

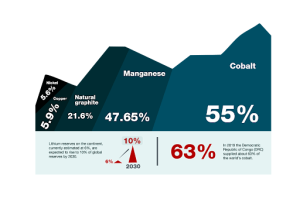

With regard to transition minerals; of the total global reserves, 55% of cobalt, 47.65% of manganese, 21.6% of natural graphite, 5.9% of copper and 5.6% of nickel are located in Africa (UNCTAD). Lithium reserves on the continent, currently estimated at 6%, are expected to rise to 10% of global reserves by 2030. Lithium and cobalt are some of the key metals used to produce batteries. In 2019 the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) supplied about 63% of the world’s cobalt. Also, the DRC and Rwanda together account for more than half of the globe’s tantalum production, a metal used in the production of mobile phones, laptops and a variety of automotive electronics.

But ownership has not necessarily translated to economic prosperity. In 1862, the United Nations General Assembly adopted resolution 1803 on the “Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources”. The resolution provides that States and international organisations shall strictly and conscientiously respect the sovereignty of peoples and nations over their natural wealth and resources. The resolution was the product of a push for the promotion and financing of economic development in under-developed countries and, secondly, in connection with the right of peoples to self-determination. More than six decades after the adoption of resolution 1803 and in spite of the vast mineral resources on the continent, African countries are still among the poorest in the world.

Much of Africa’s resource wealth is arguably under the control of entities external to the continent. Almost all the major gold mining companies in Ghana are owned by foreign investors from the USA, Canada and Australia (Nana Opong Yaw, 2022). Although Guinea has the world’s second largest reserves of bauxite, the source ore for Aluminium used in the manufacture of aircrafts, windmills and solar panels; 54.6% of the bauxite exports are controlled by Chinese companies according to Mining Technology. Historically, foreign companies dominated Nigeria’s oil and gas production, with major players like Shell, ExxonMobil and Chevron accounting for a significant portion. However, as international oil companies (IOCs) divest from onshore assets and focus on deepwater exploration, this share has been declining, with Nigerian companies now reportedly contributing about 50% of total production. Similarly, most of Zimbabwe’s lithium mines are owned by Chinese mining companies like Sinomine, Zhejiang Huayo Cobalt, Chengxin Lithium, Yahua and Canmax (The conversation).

This is not unconnected to the fact that indigenous capacity on the continent to transform its resources into meaningful products has historically been left lacking which has partly driven the appetite for international investors. Whether it is fossil fuel or renewable energy technology, Africa still operates at the extractive level of production. Primary products are shipped off-continent to manufacturing centres across the world and shipped back as finished, higher value products. Unless these dynamics change, Africa may likely remain in a perpetual fight against poverty. Cobalt, lithium, nickel for battery production and aluminium which are used in the production of solar panels can be found on the continent, but the solar cell itself is manufactured outside Africa. With a 60% year-on-year increase, the surge in renewable energy adoption on the continent is notably celebrated. However, 85% to 90% of the photovoltaic modules installed in Africa in 2023 came from China, according to IRENA’s “Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024” report. Africa manufactures neither wafers, nor cells, nor complete modules. Only a few assembly units exist, notably in South Africa (ecofin agency).

To enhance in-country manufacturing, capacity building and increased revenue, African countries have started exploring policies that promote local resource development. In May 2025, Guinea revoked over fifty mining licenses, including that of the Guinea Alumina Corporation (GAC), a subsidiary of Emirates Global Aluminium (EGA), for failing in its commitment to build a domestic alumina refinery; while Zimbabwe aims to ban the export of lithium concentrates from January 2027. Such policies tend to upset global commodity markets and supply chains, an undesirable situation for the global economy. It is evidently clear that for the energy transition to be just and inclusive for Africa, discussions at global fora like the COPs must not only address climate change adaptation, which agreeably is a major challenge on the continent, but also actively include frameworks that empower African countries to build and retain capacity, to not just harness but also develop its array of resources to get more benefits and move its citizens out of poverty.

BudgIT, through its offices across the West African region, continues to drive advocacy to strengthen Africa’s ability to achieve self-determination across economic sectors by leveraging international platforms. At the second Africa Climate Summit in Ethiopia, BudgIT brought together experts from across the continent to advance pathways that can reshape global financial structures and raw materials trade for a just energy transition on the continent.