Whether it is poor energy access, environmental pollution, mounting debt, inadequate revenue, or budget deficits, these challenges appear to be common markers in most African countries, despite owning at least 30% of the world’s minerals, including significant proportions of critical minerals such as cobalt, lithium, platinum, and manganese. For example, Africa is home to sizable reserves of the world’s critical energy transition minerals—55% of cobalt, 47.65% of manganese, 21.6% of natural graphite, 5.9% of copper, and 5.6% of nickel globally (UNCTAD). Lithium reserves, currently estimated at 6% are expected to rise to 10% of global reserves by 2030. These and many more make Africa critical to the global energy transition.

In Nigeria, a petro-dependent economy where oil and gas account for close to 60% of total revenue on average and more than 80% of exports and foreign exchange earnings, revenues are insufficient to fund national budgets for over 200 million people, resulting in borrowing, which increases debts. Nigeria’s debt-to-GDP ratio currently hovers around 50%, yet it ranks 43rd in Africa, which means that 42 out of 54 countries (77%) in Africa have debt-to-GDP ratios above 50%. Three countries had ratios over 100%, with Sudan topping the list in 2024 at 238%. Consequently, a large portion of revenues is used to service debts in many African countries, leaving very little room for human capital and social investments or infrastructural development. Energy poverty, infrastructural deficit and poor human capital development are hence symptoms of critical underlying factors that create multiplier effects observed in weak socio-economic outcomes.

Over 600 million people in Africa still lack electricity, yet public finance and infrastructure priorities remain shaped by export corridors and extractive models. From oil and gas reserves in Nigeria, Gold in Ghana, Bauxite in Guinea, Cobalt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Coffee in Ethiopia, and the vast critical agricultural and mineral resources that are scattered throughout the continent, Africa’s resources are to a considerable extent controlled by foreign businesses and predominantly shipped out of the continent—cheap and raw inputs to fuel the economies of developed nations.

While regionally, electricity access averages 53% in Africa, countries such as South Sudan, Burundi, and Chad record rates of 5.4%, 11.6%, and 12%, respectively. Close to one-third of African countries have less than 50% of electricity access (World BanK). In the DRC, less than 20% of the Congolese population has access to electricity, one of the lowest rates in the world, a concern expressed by Christian Mbenga, Energy Coordinator at Resource Matters. The mining sector consumes about 85% of all available power. Yet, even the mines face shortages of almost 1 gigawatt and often use diesel generators. In contrast, communities living right next to the cobalt and copper mines, the minerals at the centre of the global energy transition, often remain without power for schools, hospitals, or businesses.

Similar scenarios abound across the continent. Guinea possesses the second-largest bauxite reserves in the world, but it relies on foreign companies, mostly from the Western Hemisphere, to extract the resource. The situation is the same with Gold in Ghana, Coffee in Ethiopia, oil or Lithium in Nigeria. Meanwhile, close to half of Guinea’s population lacks access to electricity and lives below the poverty line.

Amidst all these, the continent also grapples with the challenges of energy transition. The majority of the population still needs electricity. Industries need to be built or expanded, and economies are in desperate need of growth. However, African governments are expected to provide the energy required to grow their economies, power industries, and support their populations, while also exploring alternatives to fossil fuels, with revenue they cannot generate without pushing the debt ceiling beyond their already precarious levels. Clearly, these do not add up.

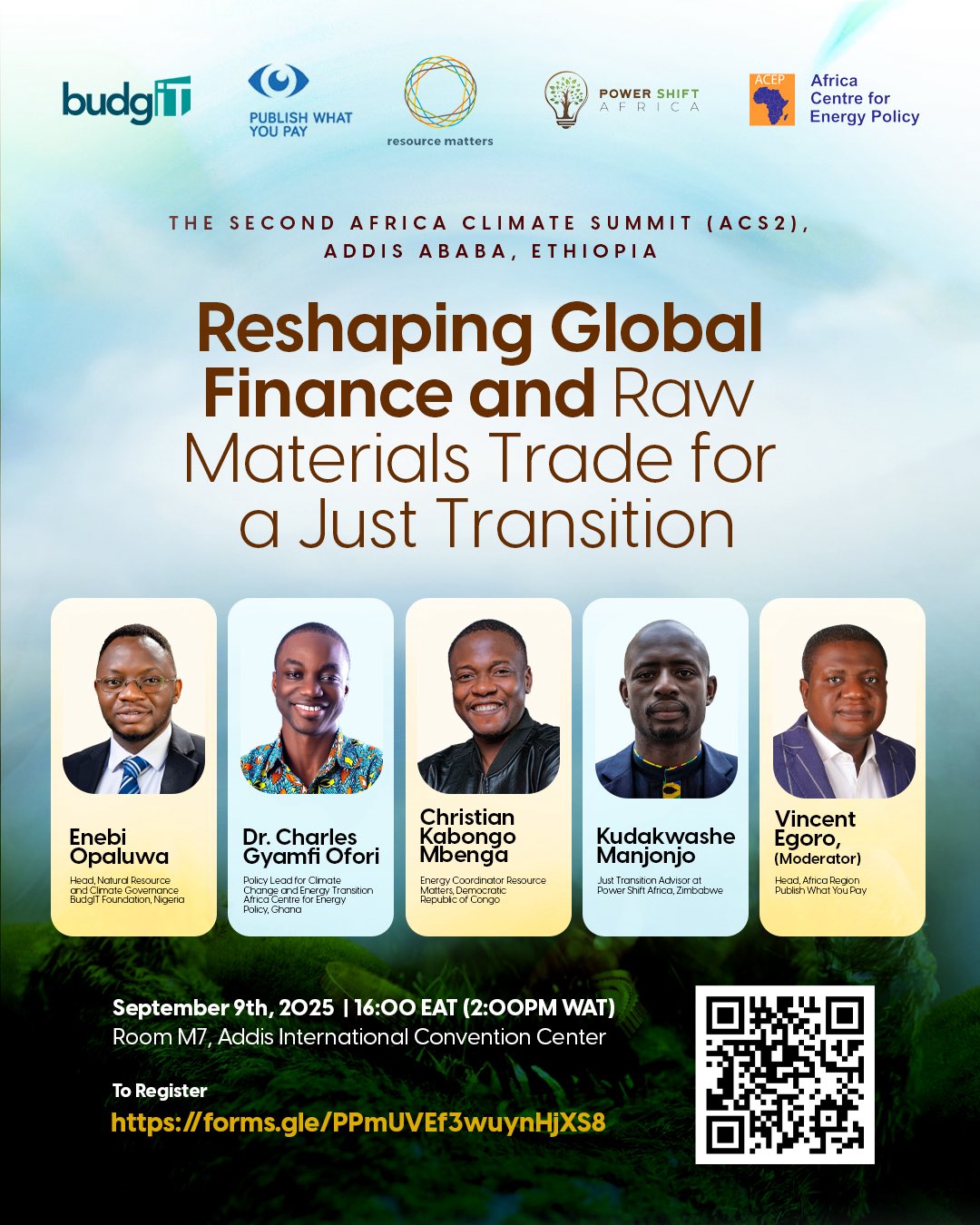

These were the issues that experts aimed to address at the panel session, “Reshaping Global Finance and Raw Materials Trade for a Just Transition,” organised by BudgIT in collaboration with the Resource Justice Network (formerly Publish What You Pay) at the second Africa Climate Summit (ACS2).

Necessary steps have to be taken to alter the trajectory of development on the African continent for better outcomes. Christian Mbenga emphasised that mineral wealth and renewable energy potential can benefit the Congolese people when managed effectively. Using tools like Congo Epela and the Makuta platform, mining royalties can be tracked and channelled to the energy needs of mining communities using sustainable energy sources.

Congo Epela makes electrification concrete by showing where and how decentralised solutions, such as hydro, solar, and wind, can work for communities, while Makuta tracks the royalties due and those actually paid by companies. With Congo Epela and Makuta together, both the energy needs and the revenues available to meet them are evident. If Congo uses its royalties wisely and invests in clean energy, it can turn non-renewable minerals into a renewable future. Transparent management and strategic allocation of mining royalties enable the DRC to transform non-renewable wealth into a sustainable asset—access to clean energy for all and a stronger tax system.

Evidently, expanding energy access requires sufficient funding, and African countries need to mobilise revenues domestically if they must finance electrification projects in a sustainable manner and with less strain on their fiscal balance.

According to Enebi Opaluwa, Head of Natural Resources and Climate Governance at BudgIT, African countries are already feeling the weight of debt on their economies. The effects of climate change, such as floods, desertification, and heatwaves, which are increasingly frequent, compound these challenges through loss of life and property damage. Yet, climate financing to Nigeria, like several other African countries, is significantly less than the estimated amount needed to combat climate change.

More worrisome is that the bulk of financing is structured as loans rather than grants, thereby worsening the debt burden of many countries that are in desperate need of funds. For example, in 2022, Nigeria received a total of $2.5 billion in climate finance (public and private capital, domestic and international). In the same year, the country’s foreign debt service bill was $2.3 billion. To make matters worse, losses due to widespread floods across the country that year were estimated at $6.6 billion (Climate Policy Initiative, 2024). Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result is nothing short of ridiculous. Stated differently, given the glaring challenges of climate change and the lack of sustainable external financing, it will be useless to continue fiscal recklessness and expect to reduce the debt burden. African countries must first manage existing resources prudently while exploring innovative ways to mobilise resources domestically and internationally.

But African governments do not have to look too far to find innovative solutions to climate finance, according to Kuda Manjonjo, Just Energy Transition Advisor at Powershift Africa, Zimbabwe. Delivering Africa’s continental masterplan will require an estimated US$1.3 trillion. Yet the continent’s financial landscape holds latent firepower in US$2.8 trillion in public pension funds, more than twice the estimated needs. This, Kuda says, shows that mobilising domestic resources is possible.

In addition, innovations such as blended finance and diaspora climate bonds, which leverage the billions already flowing through remittances, as seen in the case of Ethiopia’s Renaissance Dam, demonstrate how Africa can tap into both global and local capital to finance transformation. Furthermore, Kuda adds that regional integration is also key to leveraging resources, noting that Southern Africa and Zimbabwe already demonstrate deep mineral and industrial interdependence. Both countries together account for around 80% of global platinum output and nearly half of the world’s chrome ore. The region’s steel plants are tied through shared supply chains, underlining that industrial policy is already underway.

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) already provides this framework for regional trade integration on the continent. Charles Ofori, Policy Lead for Climate and Change and Energy Transition at the Africa Centre for Energy Policy in Ghana, analysed how the fast-growing renewable energy market can thrive through regional trade policy. Renewable energy capacity in Africa grew by over 30% between 2015 and 2020. This rapid adoption shows the potential for transformative change. The challenge is not the uptake of green technologies, but how to leverage them for poverty reduction, industrialisation, and broader economic development.

AfCFTA provides a pathway to integrate clean energy value chains. ACEP’s study on the solar PV value chain found that roughly 80% of segments meet AfCFTA’s rules of origin requirements. Except for module assembly, most components of the value chain are eligible for preferential treatment across member states. But loopholes in rules of origin can undermine value chain integration. The AfCFTA’s rules of origin (RoO) are designed to ensure that only goods and services that qualify can benefit from preferential treatment. A challenge arises when a product meets the RoO criteria but has not been liberalised in the State Party expected to grant such preferential access. Charles explains that some State Parties may exploit the gap by withholding liberalisation to sidestep the full intent of preferential treatment under the AfCFTA. Such practices undermine the spirit of the agreement, weaken trust among members, and risk slowing down the broader goals of regional integration.

Furthermore, Africa comprises 54 countries, each with its own local content policies, industrial strategies, and trade priorities. Some countries already maintain external agreements with other regions that can conflict with AfCFTA’s objectives, for example, preferential trade deals with the European Union or China that include export restrictions on critical minerals. Overcoming these challenges requires political will, harmonisation of policies, and trust among member states to align national interests with the collective goal of integrated clean energy value chains.

The Africa Climate Summit 2 represented a platform to define Africa’s priorities in transitioning to cleaner energy sources, as well as its expectations from the global community, while protecting its economies and people. Leaders on the continent must recognise the opportunities and leverage resources—human, intellectual, financial and natural—to define and preserve its place within the global economy. Kuda’s words summed it perfectly: “for Africa, the real question is whether the transition will be genuinely inclusive or an ‘elite transition’ that consolidates benefits at the top while leaving workers, communities, and informal economies behind.”

Presently, energy transition plans contain ambitious targets and signal the need for scaling technologies. But they also reveal a reality: Africa is largely a market for green technologies rather than a producer. It is time to move beyond adoption and focus on innovation, local manufacturing, and value addition. As Charles stated, “ The focus must shift from energy to value creation.” Kuda’s thoughts were equally not far off: “Energy is an enabler, not the primary market.”

If countries align policies and trade regionally, they can benefit from reduced tariffs, faster customs processes, and a more predictable market. Africa already has key competencies that can be leveraged to facilitate intra-continental trade. The answers we seek may just lie within the continent. It is our responsibility to harness the continent’s latent power and deploy it transparently and effectively to drive explosive growth. It is time to turn potential into results.