A lot has been said about the anomaly the Nigerian budget has become, and it strikes at the core of the fiscal indiscipline that has defined recent years. When projects that do not align with national objectives are inserted into the budget and remain unfunded due to revenue shortfalls, it is inappropriate to roll such projects over into subsequent fiscal years, as done with the 2024 and 2025 re-enacted acts-that are yet to be seen. Yet, this is precisely what the federal government has done. Inefficient and unfunded budget items have been allowed to persist, creating a distortion in fiscal planning. The result is a system that attempts to fully fund capital items without properly prioritising other critical obligations or correcting unrealistic assumptions.

In 2024, the federal government recorded revenue of N20.98 trillion against actual expenditure of N34.49 trillion, resulting in a deficit of N13.58 trillion. This deficit almost mirrored new borrowing for the year. Instead of formally closing the 2024 budget, the government carried it over, using 2024 revenues to fund the 2025 recurrent budget while largely financing 2024 capital projects. By June 2025, only N3.99 trillion had been utilised for the 2024 budget and N393.86 billion for the 2025 capital budget for MDAs.

The 2026 budget exhibits the underlying problems of rising deficits and weak domestic resource mobilisation remain. The federal government has proposed a total expenditure of N58.47 trillion. With revenues unlikely to exceed N23 trillion in 2025 and N28 trillion in 2026 (even under BudgIT’s generous projections), the government has once again expanded its fiscal numbers. A cursory review shows a projected deficit of N23.85 trillion against revenue of N34.3 trillion. This implies a deficit-to-revenue ratio of about 70 percent. In practical terms, for every N100 the government expects to earn, it plans to borrow N70. It signals further pressure to ramp up public debt, especially as revenue performance already lags behind projections and the federal government has shown little willingness to streamline its expenditure profile.

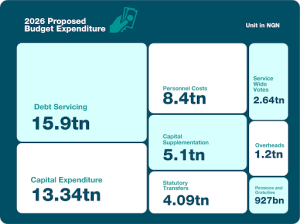

The 2026 proposed budget shows planned spending of N8.4 trillion on personnel costs, N1.2 trillion on overheads, N927 billion on pensions and gratuities, N2.64 trillion on service-wide votes, N5.1 trillion for capital supplementation, N4.09 trillion for statutory transfers, N15.9 trillion for debt servicing, and N13.34 trillion for capital expenditure across MDAs. Several issues arise from this fiscal structure that Nigerians must pay close attention to.

First, debt servicing remains a major concern. It has grown from N942 billion in 2014 to N4.2 trillion in 2021, reached N12.6 trillion in 2024, and is projected to exceed N15 trillion in 2026. This means Nigeria is unlikely to escape the 50 to 60 percent band for debt servicing as a share of revenue in the near term. Eurobond principal repayments are due in the years ahead, and interest costs continue to rise. Nigeria urgently needs a national conversation on debt management. Expanding the deficit to fund projects that are not linked to national priorities or that do not reflect efficient use of public resources only deepens this vulnerability.

Second, an increasing share of capital expenditure is now occurring outside Ministries, Departments and Agencies. This has led to greater centralisation under the Ministry of Finance through multiple intervention funds covering infrastructure, security and housing. Capital supplementation, which used to be less than N1 trillion, has risen to N5.1 trillion. Many of these items classified as capital spending are open to debate, as several do not have a shelf life beyond the current fiscal year. Projects of this nature would be better managed by MDAs to ensure accountability, clearer oversight, and more effective service delivery.

Third, there has been a sharp increase in statutory transfers to agencies under first line charge, now totalling N4.09 trillion. The National Assembly is allocated N344 billion, the Independent National Electoral Commission N1.1 trillion, the National Judicial Council N341 billion, the Ministry of Niger Delta N618 billion, Universal Basic Education N441 billion, and the Basic Health Care Provision Fund N214 billion. What remains unclear is why detailed spending plans and audited financial statements for these agencies are not consistently made public. How does an institution like INEC spend over N1 trillion of public funds without full disclosure to citizens?

A review of sectoral allocations also reflects the government’s current priorities. Security spending continues to rise, with defence allocated N3.15 trillion, the Nigerian Police N1.33 trillion, and the Ministry of Interior N696 billion. Other sectors that deserve deeper interrogation include agriculture and food security at N1.44 trillion, science and technology at N838 billion, power at N1.1 trillion, works at N3.48 trillion, Niger Delta at N1.3 trillion, education at N2.3 trillion, health at N2.1 trillion, humanitarian affairs at N462 billion, and youth development at N518 billion.

With new tax laws reducing company income tax to 25 percent and federal government concessions on VAT, revenue performance will remain under close scrutiny in 2026. The government cannot escape fiscal discipline unless it chooses to pursue unsustainable borrowing or return to central bank overdrafts, which became a feature of the previous administration. This path would only worsen inflationary pressures and weaken macroeconomic stability.

What Nigeria needs is a renewed commitment to fiscal realism. Capital spending must be streamlined and focused on projects that directly address national priorities such as energy, food security, education, health, and infrastructure. The government must also ask itself a fundamental question: what is the guiding principle behind this spending? As has become customary, the current budget is crowded with fragmented micro projects. This makes it difficult to identify a clear national vision across MDAs. When resources are spread too thinly, impact becomes diluted and accountability becomes harder to enforce. As the 2026 Appropriation process advances, the National Assembly must exercise restraint, while the Executive must recommit to transparency, accountability, and realistic fiscal planning.

Without this reset, the national budget will cease to be a tool for development and instead become a record of deferred promises, rising debt, and missed opportunities for the Nigerian people.